In 1879, Peru got involved in the matter as a mediator, attempting to help peacefully resolve the dispute between Bolivia and Chile (though it is argued that Peru attempted to favor Bolivia at the expense of Chile). Nonetheless, in 1873 Bolivia and Peru had signed a secret defensive alliance, which some historians consider offensive and aimed at Chile, which was to bind their military forces together in the extreme case their respective territories were invaded by another nation. When Chile invaded the Bolivian port city of Antofagasta on February 14 of 1879, a military maneuver which had been done without a prior declaration of war, Bolivia called for the activation of its defensive alliance with Peru. However, war would not be formally declared by either side until Chile, which had received an official acknowledgement of the secret defensive alliance by the Peruvian government, declared war on April 5 of 1879; Peru responded the following day by declaring the casus foederis, or activation, of the alliance treaty.

The resulting five year war took place over a variety of terrain, beginning in the Atacama Desert of Bolivia and, later, as the Chilean forces advanced further north, into the deserts and mountainous regions of Peru. The first battle of the war, the Battle of Topáter, in which Chilean troops faced a defending force of Bolivian soldiers and civilians, took place before any declaration of war had been made by either side. However, once war had been declared, for most of the first year there was a focus on the Naval Campaign due to the strategic advantage of holding control of the seas in order to provide naval assistance to the land forces which would be battling in the world's driest desert. Even though the Peruvian Navy met with initial success, the naval campaign was eventually won by the Chilean Navy upon the capture of the Peruvian flagship monitor Huáscar and the death of Peru's prominent admiral Miguel Grau, known by all sides of the conflict as the "Knight of the Seas" due to his chivalry. Afterwards, the Land Campaign would result in a series of victories for the Chilean Army over the badly equipped troops of the Bolivian and Peruvian armies, which resulted in the complete defeat of Bolivia in the Battle of Tacna of May 26, 1880, and the defeat of the Peruvian regular army after the Battle of Arica in June 7 of the same year. The land campaign reached its climax in 1881, with the Chilean occupation of Lima.

Afterwards, the remaining three years of the conflict turned into a guerrilla war between a union of what was left of the Peruvian army and some irregular troops under the command of General Andrés Avelino Cáceres, and the military forces of Chile with their base in Lima under the command of Admiral Patricio Lynch. The ensuing conflict would be known as the Campaign of the Breña (or Sierra, both which make reference to the Andes' rough terrain), and would be fairly successful as a resistance movement but inneffective in changing the course of the war. Eventually, after the defeat of Cáceres in the Battle of Huamachuco, Chile and Peru managed to reach a diplomatic solution on October 20, 1883, with the signing of the Treaty of Ancón (becoming effective in 1884). Bolivia, which had abandoned Peru following the battle of Tacna, would eventually sign a truce with Chile in 1884.

Ultimately, the peace treaty led to the Chilean acquisition of the Peruvian territory of Tarapacá, the disputed Bolivian department of Litoral (leaving Bolivia as a landlocked country), as well as temporary control over the Peruvian provinces of Tacna and Arica. In 1904, Chile and Bolivia would sign a "Treaty of Peace and Friendship" which would establish the definite boundaries between both nations; nevertheless, Bolivian national sentiment to this day seeks the return of their former coast. However, the situation between Chile and Peru would take a step for the worse when the 1893 plebiscite that was going to determine the fate of the provinces of Arica and Tacna was not held, and news of a massive colonization and violent "Chilenization" of the territories resulted in a break of relations between both nations in 1911. A solution was finally accorded in the 1929 Tacna–Arica compromise which gave Arica to Chile and Tacna to Peru, but there still exist deep feelings of antipathy between both nations. The War of the Pacific has left deep scars on all sides involved, with much modern political problems among these neighboring nations generally referring back to this conflict.

| War of the Pacific | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

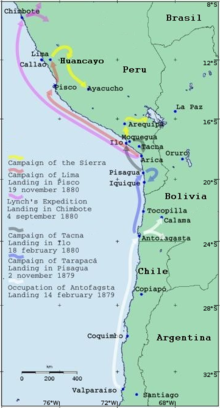

Map showing changes of territory due to the war | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| President of Peru President of Bolivia | President of Chile | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 1879 Bolivian Army: 2,300 soldiers Bolivian Navy: None Peruvian Army: 4,700 soldiers Remington and Minie rifles, Blakely cannon Peruvian Navy: 2 ironclad, 1 corvette, 1 gunboat December 1880 Peruvian Army: 28,000 soldiers[1] Peruvian Navy: None | 1879 Chilean Army: 4,000 soldiers Comblain rifle, Krupp cannon Chilean Navy: 2 battleships, 4 corvettes, 1 gunboat, 1 schooner December 1880 Chilean Army: 41,000[2](p263) soldiers Chilean Navy: 2 battleships, 3 ironclads, 4 corvettes, 2 gunboats | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 10,467 Killed/Wounded (9,103[3] POWs) Pisagua, Iquique, Mollendo, Supe, Chorrillos, Miraflores, Concepcion, San Pablo, bombed or burned | |||||||||

Contents[hide]

|

[edit] Background

Main article: Background of the War of the Pacific

See also: Boundary Treaty of 1866 between Chile and Bolivia, Treaty of defensive alliance between Peru and Bolivia of 1873, and Boundary Treaty of 1874 between Chile and Bolivia

The dry climate of the Peruvian and Bolivian coasts had permitted the accumulation and preservation of vast amounts of high-quality nitrate deposits such as guano and saltpeter. In the 1840s, the discovery of the use of guano as a fertilizer and saltpeter as a key ingredient in explosives made the Atacama desert strategically and economically valuable. Bolivia, Chile and Peru suddenly found themselves sitting on the largest reserves of a resource that the world needed.During the Chincha Islands War (1864–1866), Spain, under Queen Isabella II, attempted to use an incident involving Spanish citizens in Peru to dominate the guano-rich Chincha Islands and re-establish Spanish influence over an area that they had previously controlled with the Viceroyalty of Peru. Peru and Chile signed a defensive and offensive alliance against Spain in December 5, 1865.[4] Together, with the minor aid of Bolivia and Ecuador (who had previously had an inconclusive war with Peru from 1858 to 1860), they forced the Spanish to withdraw after achieving victories at Papudo, Abtao, and Callao. Chile, however, had to endure terrible losses after the bombardment of Valparaiso by the Spanish fleet on 31 March 1866.

While during this time Peru and Chile enjoyed an alliance based on mutual interests, a conflict between Bolivia and Chile developed because no permanent borders had been established between both nations. Claiming their borders according to the uti possidetis principle, Bolivia and Chile disagreed on whether the territory of Charcas, originally part of the Viceroyalty of Peru and, later, part of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, had access to the sea. Eventually, the two countries negotiated the Boundary Treaty of 1866 (commonly referred to as the "Treaty of Mutual Benefits") that established the 24th parallel south as their mutual boundary,[5] and entitled Chile and Bolivia equal rights to share the tax revenue on mineral exports from the territory between the 23rd and 25th parallels, which comprised a large part of the Atacama Desert. In 1872, Peru began to get involved in the dispute when it attempted to use its naval power to help Bolivia obtain a definite boundary.[6]

Atacama quickly became populated by Chilean investors backed by European capital (mainly British). The natural barrier of the Andes mountains divided the Bolivian altiplano from Atacama, so that the Bolivians were not able to colonize the area with so many settlers. Chilean and foreign enterprises in the region eventually extended their control all the way to the Peruvian saltpeter mines. During the 1870s, Peru decided to capitalize on the guano exploitation and nationalized all industries in the region, which caused Peru to hold 58.8% of all saltpeter production while Chile held 19% and Great Britain 13.5% of the total.[7] After the War of the Pacific, Peru was left without saltpeter production, the Chilean production decreased to 15%, and Great Britain's production rose to 55%.[7]

On February 6, 1873, Peru and Bolivia signed a treaty of defensive alliance which guaranteed the independence, sovereignty and the integrity of their territories, and obliged them to defend each other against all foreign aggression. An additional clause kept the treaty secret among the allies.[8] Argentina had begun talks with Peru and Bolivia to join the alliance, and the Chamber of Deputies, in a secret session, approved the law, but the Argentine Senate postponed the matter to 1874. Chile was not directly mentioned in the text of the treaty, but was not informed about its existence, which leads Chilean historiography to explain that the treaty was in reality aimed against Chile.[9]

In 1874, Chile and Bolivia superseded the boundary treaty signed in 1866 with a new boundary treaty granting Bolivia the authority to collect full tax revenue between the 23rd and 24th parallels, fixing the tax rates on Chilean companies for 25 years and calling for Bolivia to open up.[5] Heavy British capital investment drove development through the area, and most of the exploitation of the coastal region of Atacama was conducted by Chilean companies and British investments. On December 26, 1874, the recently built ironclad Cochrane arrived in Valparaiso; it remained in Chile until the completion of the Blanco Encalada, throwing the balance of power in the south Pacific Ocean towards Chile.[10] In 1875 Peru postponed the Argentine signing of the alliance treaty.[11]

[edit] Crisis

A major crisis took place in 1878 when the National Congress of Bolivia and a National Constituent Assembly found an 1873 contract authorizing the Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company to extract saltpeter duty-free for 15 years to be incomplete because it had never been ratified by the Bolivian Congress, as required by the constitution of 1871. The Bolivian Congress proposed to approve the contract only if the company would pay a 10 cents tax per quintal of mineral extracted,[12][13] but the company complained the increased payments were illegal and demanded an intervention from the Chilean government which,[14] in response, claimed the border treaty of 1874[15] did not allow for such a tax hike; the Bolivian government then suspended the tax in April 1878. In November 1878, Chilean government suggested the possibility of nullifying the Treaty of 1874 if Bolivia continued to insist on tax law; the Bolivian government then said the tax was unrelated to the Treaty of 1874 and that the claim of the Nitrate Company should be treated in Bolivian courts, reviving the tax[14]. When the Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company refused to pay the tax, the Bolivian government under President Hilarión Daza threatened to confiscate its property and, in December 1878, Chile sent a warship to the area.After the company failed to pay the tax, Bolivia announced the seizure and auction of the Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company on February 14, 1879. Chile threatened that such an action would render the border treaty null and, on the day of the auction, 500 Chilean soldiers arrived by ship and occupied the Bolivian port city of Antofagasta,[16] without a fight.[16] According to Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre, not only did the Chilean troops occupy the city without any major resistance, but they also received widespread support and encouragement.[17] Antofagasta's population was 93%-95% Chilean.[18]

On February 18, while in Antofagasta, Chilean colonel Emilio Sotomayor intercepted a letter directed to Bolivian prefect-colonel Severino Zapata from Hilarión Daza that mentioned, according to Chilean historian Gonzalo Bulnes, Daza's worry of Chilean intervention in Bolivia's nationalization of British saltpeter companies in the region, and made mention of a secret treaty that they would, if necessary, demand that Peru must honor in case Chile declared war.[19] After the Chilean soldiers arrived in Antofagasta, Hilarión Daza made a presidential decree on March 1, 1879, which demanded the expulsion of Chileans, the nationalizing of Chilean private property and prohibited trade and communications with Chile "as long as the war lasts".[20] Due to its aggressiveness the Chilean government understood the decree as a declaration of war.[21][22] However, although both nations had already taken aggressive actions, in reality no war had yet been formally declared by either side of the conflict.[23][24] Bolivia then requested Peru to activate the treaty of 1873 as they felt that the Chilean arrival in Antofagasta constituted a casus foederis of the alliance.[25]

Peru attempted to peacefully mediate the conflict by sending a senior diplomat, Jose Antonio Lavalle to negotiate with the Chilean government and request that Chile to return Antofagasta to Bolivian authorities. The Chilean government stalled negotiations, suspecting that Peru's mediation was not bona fide, and that it was only trying to gain time while it hurried its war preparations. Previous Peruvian demands had favored Bolivia and Lavalle denied knowing about the existence of a secret treaty, which seemed suspicious to the Chileans.[26][27] On March 14, Alejandro Fierro, Chile's minister of foreign affairs, sent a telegram to the Chilean representative in Lima, Joaquin Godoy, requesting immediate neutrality from the Peruvian government.[28] On March 17, Godoy formally presented the Chilean proposal in a meeting with Peruvian president Mariano Ignacio Prado who,[29] the following day, told Godoy that there existed a secret treaty allying Peru with Bolivia.[26]

A few days later, on March 23, 1879, while on their way to occupy Calama, north of 23rd parallel, 554 Chilean troops and cavalry were opposed by 135 Bolivian soldiers and civilian residents dug in at two destroyed bridges next to the nearby Topáter river. This Battle of Topáter became the first battle of the war, and the Bolivian troops under the command of Dr. Ladislao Cabrera refused to listen to calls of surrender prior and during the battle. Outnumbered and low on ammunition, most of the Bolivian force withdrew except for a small group of civilians who led by Colonel Eduardo Abaroa, fought to the end. No further land battles would take place until the war at sea was resolved.[30]

On March 24, Peru responded to Chile and Bolivia by proposing that the Peruvian Congress debate both Chilean proposal for neutrality and the Bolivian request for military action under the alliance on April 24.[31] On March 31, after receiving the treaty from Lima, Lavalle proceeded to read the whole text to Fierro and told him that it was not offensive to Chile.[26] Acknowledging its awareness of the Bolivia-Peru alliance, Chile responded by breaking diplomatic ties and formally declaring war on both Bolivia and Peru on April 5, 1879. On April 6, Peru declared casus foederis of the alliance treaty, stating that it had officially come into effect.[26][32]

[edit] The War

[edit] Military strength comparison

| Warship | tons (L.ton) | Horse- power | Speed (Knots) | Armour (Inch) | Main Artillery | Built Year |

| 3,560 | 2,000 | 9-12,8 | up to 9 | 6x9 Inch | 1874 | |

| 3,560 | 3,000 | 9-12,8 | up to 9 | 6x9 Inch | 1874 | |

| 854 | 200 | 8 | wood | 16x32-2x12-pounders | 1855 | |

| 1,101 | 300 | 12 | wood | 3x115-2x70-2x12-pounders | 1874 | |

| 1,101 | 300 | 11 | wood | 1x115-2x70-2x12-pounders | 1874 | |

| 412 | 140 | 7 | wood | 2x70-3x40-pounders | 1859 | |

| 772 | 260 | 11,5 | wood | 1x115-1x64-2x20-pounders | 1874 | |

| 1,051 | 300 | 8 | wood | 3x115-3x30-pounders | 1870 | |

| 1.130 | 1,200 | 10-11 | 4½ | 2x300-pounders | 1865 | |

| 2,004 | 1,500 | 12-13 | 4½ | 2x150-pounders | 1865 | |

| 1.034 | 320 | 6 | 10 | 2x500-pounders | 1864 | |

| 1.034 | 320 | 6 | 10 | 2x500-pounders | 1864 | |

| 1.150 | 320 | 13 | wood | 12x68-1x9-pounders | 1864 | |

| 600 | 180 | 10,5 | wood | 2x70-4x40-pounders | 1864 |

The Bolivian Army numbered no more than 2175 soldiers, divided into three infantry regiments, two cavalry squadrons, and two sections of artillery.[37] The Colorados Battalion, President Daza's personal guard, was armed with Remington Rolling Block rifles, but the remainder of the infantry was armed with odds and ends including flintlock muskets. The artillery had three rifled pounders and four machine guns, while the cavalry rode mules because the shortage of good horses.[36]

The regular Chilean Army was well equipped,[38][39][40][41], with 2694 manpower. By April 5, the day when Chile formaly declared war on Peru and Bolivia, the army had swelled to 7906 men. The regular infantry was armed with the modern Belgian Comblain rifle, of which Chile had a stock of some 13000. Chile also had Grass, Minie, Remington and Beaumont rifles which mostly fired the same caliber cartridge (11 millimeter). The artillery had seventy-five artillery pieces, most of which were of Krupp and Limache manufacture, and six machine guns. The cavalry used French sabers and Spencer and Winchester carbines.[42]

[edit]

Main article: Naval Campaign of the War of the Pacific

Given the few roads and railroad lines, the nearly waterless and largely unpopulated Atacama Desert was difficult to conquer and occupy for long. From the beginning of the war it became clear that, in order to achieve control of the local nitrate industry in a difficult desert terrain, control of the sea would prove to be the deciding factor of the war.[43] Since Bolivia did not count with any military vessels,[44] despite that on March 26 of 1879 Hilarión Daza formally offered letters of marque to any ships willing to go to combat for Bolivia,[45] the naval conflict was left to be resolved between the Armada de Chile and the Marina de Guerra del Perú.The power of the Chilean navy was based on the twin armored frigates, Cochrane and Blanco Encalada, each of 3,560 tons and equipped with 6x250 pound muzzle-loading guns, 2x70 pound guns, 2x40 pound guns, and an armored belt with a maximum thickness of 9 inches.[46] The ships' maximum operating speed was about 12 knots.[34][47] The rest of the fleet was formed by the corvettes Chacabuco, O'Higgins, and Esmeralda, the gunboat Magallanes, and the schooner Covadonga.[48]

The Peruvian navy based its power on the armored frigate Independencia and the monitor Huáscar.[46][49] The Independencia weighed 3,500 tons, with 4 ½ inch armor, 2x150 pound guns, 12x70 pounders, 4x32 pounders, and 4x9 pound guns.[48] Her maximum operating speed was about 12 knots.[34][47] The monitor Huáscar weighed 1,745 tons, had 4 ½ inch armor and possessed 2 muzzle-loading 300 pound guns located in a revolving turret. She had a maximum operating speed of 10 or 11 knots.[34][47] The rest of the fleet was completed by the corvette Unión, the gunboat Pilcomayo, and the fluvial monitors BAP Atahualpa and BAP Manco Cápac.[48] Although both the Chilean and Peruvian ironclads seemed evenly matched, the Chilean ironclads had twice the armor and held a greater range and hitting power.[49]

In one of the first naval tactical moves of the war, on April 5, 1879 the Peruvian port of Iquique was blocked by the Chilean Navy.[50] What followed was the first naval encounter of the war, the indecisive Battle of Chipana of April 12, 1879, in which the Chilean corvette Magallanes escaped the Peruvian vessels Unión and Pilcomayo, but was unable to complete its reconnaissance mission. In the Battle of Iquique, which took place on May 21, 1879, the monitor Huáscar, under the command of Captain Miguel Grau Seminario, managed to sink the Chilean corvette Esmeralda. Esmerelda's commander, Commander Arturo Prat Chacón, died in combat and became Chile's greatest naval hero.[51] At around the same time, the Peruvian frigate Independencia, led by Captain Juan Guillermo More, chased the Chilean schooner Covadonga (Lieutenant Commander Carlos Condell) into shallow coastal zones which eventually caused the heavier Independencia to wreck at the Punta Gruesa.[52] The naval battles of Iquique and Punta Gruesa gave a tactical victory to Peru: the blockade of the port of Iquique was lifted and the Chilean ships retreated or were sunk.[53] Nevertheless, it was a Pyrrhic victory; the loss of the armored frigate Independencia, one of most important ships of the Peruvian navy, represented an irreparable blow for Peru.[52]

Despite being outnumbered, the Huáscar, under the command of Grau, managed to hold off all of the Chilean navy for six months.[54] During this time the Huáscar participated in the Battle of Antofagasta (May 26, 1879) and the Second Battle Antofagasta (August 28, 1879).[55] The climax finally came with the capture of the steamship Rímac on July 23, 1879.[56] Rímac was captured with a cavalry regiment on board (the Carabineros de Yungay), making this the largest loss the Chilean army had thus far had in the war.[57] This caused a crisis in the Chilean government which leading to the resignation of admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo.[58][59] The command of the Chilean fleet was then handed to Commodore Galvarino Riveros Cárdenas,[58][60] who devises a plan to catch the Huáscar.[61]

The decisive battle of the sea campaign took place in Punta Angamos, on October 8, 1879.[62] In this battle, the monitor Huáscar was finally captured by the Chilean Navy, despite the attempts of her crew to scuttle her.[63] Miguel Grau Seminario died during the fighting, but he becomes a national hero in Peru.[64] However, the Peruvian navy would go on to achieve victories at the Naval Battle of Arica (February 27, 1880) and the Second Naval Battle of Arica (March 17, 1880), before finally being completely defeated during the Blockade of Callao,[65] where the Peruvian fleet was set on fire and the coastal defenses of Callao were destroyed or taken to Chile.[66][67]

[edit] Campaign of Tarapacá

Once the naval superiority was achieved, the troops of the Chilean army began the occcupation of the Peruvian province of Tarapacá.On 2 November 1879 at 7:15 they began a naval bombardment and started landing troops at the small port of Pisagua and the Junin Cove, –some 500 km north of Antofagasta. At Pisagua, several landing waves Chilean troops attacked beach defenses held by Allies, and took the town. By the end of the day, the Chilean army were ashore and moving inland[2](p172-)

From Pisagua the Chileans marched south towards the city of Iquique with 6,000[citation needed] troops and defeated on 19 November 1879 the 7,400[citation needed] allied troops gathered in Agua Santa in Battle of San Francisco/Dolores. Bolivian forces retreated to Oruro and the Peruvians to Tiliviche. Four days later, the Chilean army captured Iquique without resistance.

A detachment of 3,600[citation needed] Chilean soldiers, cavalry and artillery, was sent to face the Peruvian forces in the small town of Tarapacá. Peruvian forces started a march towards Arica to find Bolivian troops led by Hilarión Daza coming from Arica southwards, but in Camarones Daza decided to return towards Arica.

Chileans and Allies met on 27. November 1879 in the Battle of Tarapacá, where the Chilean forces were defeated,[68] but the Peruvian forces, unable to maintain the territory, retreated further north to Arica by 18 December 1879.[69]

About the importance of the campaign Bruce W. Farcau wrote:

- "The province of Tarapacá was lost along with a population of 200,000, nearly one tenth of the Peruvian total, and an annual gross income of ₤ 28 million in nitrate production, virtually all of the country's export earnings."[70](p119)

[edit] Downfall of Prado and Daza, and the election of Santa Maria

The Peruvian government was confronted with widespread rioting in Lima because of the disastrous handling of the war to date[72].On 18 December 1879 the Peruvian President Mariano Ignacio Prado suddenly took a ship from Callao to Panama, allegedly with six million pesos in gold[73], supposedly to oversee the purchase of new arms and warships for the nation. In a statement in the newspaper El Comercio he turned over the command of the country to Vice President La Puerta. After a putsch and more than 300 dead[74] Nicolás de Piérola overthrew La Puerta and took power in Peru on 23 December 1879.

Back to Arica from the aborted expedition to Iquique, on 27 December 1879 Daza received a telegram from La Paz informing him the army had overthrown him. He departed to Europe with $500,000. In Bolivia General Narciso Campero became president.[75]

Bolivia's president Campero remained in office until the end of the war, but Pierola was recognized as president only by his occupation of Lima.

During the Bolivian tax crisis of 1879, Chile voted a new Congress on schedule and in 1881 Domingo Santa Maria was elected as President of the Republic. He assumed the office on September 18, 1881 A new Congress was elected in on schedule in 1882.[76]

[edit] Campaign of Tacna and Arica

After the failure of the peace talks the Chilean forces began to prepare for the occupation of South Peru. On 28 November 1879[2](p214) Chile declared the formal blockade of Arica. Later the port Callao was also put under blockade.

A Chilean force of 600 men carried out an amphibious raid at Ilo as a reconnaissance in force, to the north of Tacna, on December 31, 1879, and withdrew the same day.[77]

On 24 February 1880 approximately 11,000 men in nineteen ships protected by the warships Blanco Encalada, Toro and the Magallanes and two torpedo boats sailed from Pisagua and arrived off Punta Coles, near Pacocha, Ilo on 26 February 1880. The landing took several days and occurred without resistance The Peruvian commander, Lizardo Montero, refused to try to drive the Chileans from the beachhead, as the Chileans had expected.[2](p217)

On 22 March 1880 3,642 Chilean troops defeated 1,300[2](p222) Peruvian troops in the Battle of Los Ángeles cutting any direct Peruvian supply from Lima to Arica or Tacna[78] (Supply was possible only through the long way over Bolivia).

After the Battle of Los Ángeles there were three allied positions in South Peru. General Leyva's 2nd Army was at Arequipa, with some survivors of the battle at Los Angeles included. Bolognesi's 7th and 8th Division was at Arica and at Tacna was the 1st Army. All these forces were under the direct command of the Bolivian president, Campero.[79] But they were unable to concentrate troops or even to move from their garrisons.[80][81]

After crossing 40 miles (64 km) of desert, on 26 May 1880 the Chilean army (14,147 men[2](p229)) destroyed the allied army of 5,150 Bolivians and 8,500 Peruvians in the Battle of the Halt of the Alliance.

The need for a port near the army to supply and reinforce the troops and evacuate the wounded made the Chilean command concentrate on the remaining Peruvian stronghold of Arica. On June 7, 1880, after the Battle of Arica, the last Peruvian bastion in the Tacna Department fell.

After the campaign of Tacna and Arica, the Peruvian and Bolivian regular armies ceased to exist.[2](p256) Bolivia effectively dropped out of the war.[70](p147)

[edit] Lackawanna Conference

Prior to the United States becoming formally involved into the matter, the united proposal of France, England, and Italy was to provide Chile with Tarapacá while they retreated their troops to the Camarones River; Chile found this solution to be acceptable.[82]On October 22, 1880, delegates of Peru, Chile, Bolivia, and the Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States of America in Chile held a 5-day conference aboard the USS Lackawanna in Arica.[70](p153) The Lackawanna Conference, also called the Arica conference, attempted to develop a peace settlement for the war. Chile demanded the Peruvian Tarapacá province and the Bolivian Atacama, an indemnity of $20,000,000 gold Pesos, restoration of property taken from Chilean citizens, the return to Chile of the transport vessel Rimac, the abrogation of the alliance treaty between Peru and Bolivia and the formal commitment on the part of Peru not to mount artillery batteries in Arica's harbor once it was returned by Chile. Furthermore, Arica was to be limited to commercial use only. Celae planned to retain all the territories of Moquegua, Tacna, and Arica until all peace treaty conditions were satisfied. Although willing to accept the negotiated settlement, Peru and Bolivia insisted that Chile withdraw its forces from all occupied lands as a precondition for discussing peace. Having captured this territory at great expense, Chile refused to accept these terms and the negotiations failed.

[edit] Lynch's Expedition

To show Peru the futility of further resistance against Chilean forces, on 4 September 1880 the Chilean government dispatched an expedition of 2,200 men [83] to northern Peru under the command of Captain Patricio Lynch to collect war taxes from wealthy landowners.[84][85] Lynch's Expedition arrived on 10 September to Chimbote[2](p260-) levied taxes of $100,000 in Chimbote, $10,000 in Piata, $20,000 in Chiclayo, and $4,000 in Lambayeque in local currencies; those who did not comply had their property impounded, destroyed or were killed. On September 11, 1880, the Peruvian government made a decree that made the payment of these taxes an act of treason, but most land owners still paid the Chileans under death threats and the belief that denizens of occupied areas had to comply with the occupying army.[86][edit] Campaign of Lima

Main article: Occupation of Lima

After the campaign of Tacna and Arica, the southern departments of Peru were in Chilean hands, and the allies armies were smashed, so for the Chilean government there was no reason to continue the war. However, public pressure as well as expansionist ambitions pushed the war farther north.[87][88] The defeated allies not only didn't realize their situation, but despite the empty Bolivian treasury, on 16 June 1880 the National Assembly voted in favour of a continuation of the war and on 11 June 1880 was signed in Peru a document declaring the creation of the United States of Peru-Bolivia.[89]

This forced both the Chilean government and its high command to plan a new campaign with the objective to obtain an unconditional capitulation at the Peruvian capital city.[90]

The Chilean forces would have to confront virtually the entire civilian male population of Lima defending prepared positions and supported by a formidable collection of the coastal guns of Lima, located within a few miles of the capital's arsenal and supply depots.[2](p258-259) President Pierola ordered the construction of two parallel lines of defenses at Chorrillos and Miraflores a few kilometers south of Lima. The line of Chorrillos had 10 miles (16 km) long, lying from Marcavilca hill to La Chira, passing through the acclivities of San Juan and Santa Teresa[2](p276-). The Peruvian forces were approximately 26,000 untrain civilian men between Arequipa and Lima.[91]

A small Chilean force went ashore near Pisco, approximately 200 miles (322 km) South of Lima, and the mass of the army disembarked in Chilca only 45 kilometers (28 mi) from Lima.

On January 13, 1881 the 20,000[92] Chilean troops charged 14,000[92] Peruvian defenders in Chorrillos. During the Battle of Chorrillos, the Chileans inflicted a harsh defeat to the Peruvian militia and eliminated the first defensive line guarding Lima. Two days later, on January 15, 1881, after the triumph in the Battle of Miraflores the Chilean army entered Lima.

After the battle there were fires and sackings in the towns of Chorrillos and Barranco.

[edit] Occupation of Peru

Chileans troops entered Lima on 17 January 1881.[2](p296). The Peruvian dictator Nicolás de Piérola retreated from the capital to try governing from the rear area, and he still refused to accept Chile's demand for territory and indemnity.[93]In absence of a Peruvian president who was willing to accept their peace terms, on February 22, 1881, the Chileans allowed a convention of Peruvian "notables" outside of Lima that elected Francisco García Calderón as president. Garcia Calderón was allowed to raise and arm two infantry battalions (400 men each) and two small cavalry squadrons to give more legitimacy to the provisional government.[70](p173)

The commander of the Chilean occupation, Vice-admiral Patricio Lynch, set down his military headquarters in the Government Palace of Peru in Lima. After the confrontations in San Juan and Miraflores, Peruvian Colonel Andrés Avelino Cáceres decided to escape to the central Andes to organize and reinitiate the Peruvian resistance to the Chilean occupation army from within the mountain range. This would come to be known as the Campaign of the Breña or Sierra, which organized abundant acts of rebellion in Lima and eventually organized a widespread Peruvian resistance.[94][95]

Meanwhile, in Chile the new administration under the command of Domingo Santa Maria pushed for an end to the costly war.

[edit] Letelier's expedition

In February 1881, the Chilean forces under the command of Lt. Col. Ambrosio Letelier started the first Expedition, with 700 men, to defeat the last guerrilla bands from Huanuco (30 April) to Junin. After many loses the expedition achieved very little and came back to Lima in early July[2](p309-), where Letelier and his officers were court-martialed because they illegally diverted money into their own pocket.[96][edit] First campaign of La Sierra

To annihilate the guerrilla, Lynch started in January 1882 a new offensive with 5,000 men[2](p315-) first in direction Tarma and then southeast: Huancayo, until Izcuchaca. The Chilean troops suffered enormous hardships: cold, snow, mountain sickness (more than 5,000m). On 9 July 1882 was fought the emblematic Battle of La Concepción. The Chileans had to pull back with a lost of 534 soldiers: 154 died in combat, 277 died to disease and 103 deserted.[edit] Rise of Miguel Iglesias

During the administration of James A. Garfield (Mar. 4, 1881 – Sep. 19, 1881) in the USA, the anglophobic Secretary of State James G. Blaine wanted to advance the US presence in Latin America. He believed that England had prodded Chile into war on Peru to secure England's stake in the mineral weath of the disputed areas. Blaine made a proposal that called for Chile to accept a monetary indemnity and renounce claims to Antofagasta and Tarapacá. These American attempts reinforced Garcia Calderon's refusal to discuss the matter of territorial cession. When it became known that Blaine's representative to Garcia Calderone, Stephen Hurlburt, would personally profit from the business trade-off, it was clear that Hurlburt was complicating the peace process.[97]Because of President Calderon's refusal to relinquish Peruvian control over Tarapacá, he was placed under arrest. Before Garcia Calderon left Peru for Chile, he named Admiral Lizardo Montero as successor. At the same time President Pierola stepped back and supported Avelino Caceres for the Presidency of Peru. Caceres refused to serve and supported Lizardo Montero instead. Montero moved to Arequipa and in this way Garcia Calderon's arrest achieved the union of the forces of Pierola and Caceres.[2](p329)

Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen, successor to Blaine as US Secretary of State after the assassination of President Garfield, publicly disavowed Blaine's policy while abandoning any notion of intervening militarily in the dispute[2](p306) and recognizing Chile's right to annex Tarapacá.[2](p329)

On 1 April 1882 Miguel Iglesias, former Defence minister under Pierola, became convinced that the war had to be brought to an end if Peru was not to be completely devastated. He issued a manifesto, "Grito de Montan", calling for peace and in December 1882 called a convention of representatives of the seven departments of northern Peru where he was elected "Regenerating President"[2](p329-330)[70](p181-182)

[edit] Second campaign of La Sierra

To protect and support Iglesias against Montero, on 6 April 1883, Patricio Lynch started a new offensive to drive the Montoneros from central Peru and destroy Caceres' little army. Unlike in previous plans, the Chilean troops pursued Caceres to northwest through narrow mountain passes until 10 July 1883 as the definitive Battle of Huamachuco was fought. The Peruvians were defeated.[2](p317-338)[70](p183-187) It was the last battle of the war.[edit] End of Occupation

After the signing of the peace on 20 October 1883 with the government of Iglesias, Lizardo Montero tried to resist in Arequipa, but fortunately for Chile, the arrival of |the {???} its| men stampeded Montero's troops and Montero went for a Bolivian asylum.[98]On 29 October 1883 ended the Chilean occupation of Lima.

[edit] Peace

[edit] Peace treaty with Peru

On October 20, 1883 hostilities between Chile and Peru formally came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Ancón. Under the terms of the treaty Chile was to occupy the provinces of Tacna and Arica for 10 years, after which a plebiscite was to be held to determine nationality. The two countries failed for decades to agree on the terms of the plebiscite. Finally in 1929, through the mediation of the United States under President Herbert Hoover, an accord was reached by which Chile kept Arica. Peru reacquired Tacna and received some concessions in Arica.[edit] Peace treaty with Bolivia

In 1884, Bolivia signed a truce that gave control to Chile of the entire Bolivian coast, the province of Antofagasta, and its valuable nitrate, copper, and other mineral deposits, and a further treaty in 1904 made this arrangement permanent. In return, Chile agreed to build a railroad connecting the capital city of La Paz, Bolivia with the port of Arica, and Chile guaranteed freedom of transit for Bolivian commerce through Chilean ports and territory.[edit] International Law of War

The three nations involved in war adhered to the Geneva Red Cross Convention to protect the war wounded, prisoners, refugees, civilians, and other non-combatants.[99]At that time there was no other binding international law between both countries about this issue. Nevertheless, there were accusations of atrocities by all three parties to the war.

[edit] Strategy and technology

It was clear from the beginning that strategic control of the sea would be the key to an inevitably difficult desert war: supply by sea, including water, food, ammunition, horses, fodder and reinforcements, was quicker and easier than marching supplies through the desert or across the Bolivian high plateau. While the Chilean Navy started an economic and military blockade of the Allies' ports, Peru took the initiative and used its smaller but still-effective navy as a raiding force. Chile was forced to delay the ground invasion for six months, and to shift its fleet from blockading to hunting the Peruvian ship Huascar until it was captured. After achieving naval supremacy, sea-mobile forces proved to be an advantage for desert warfare on a long coastline. Peruvian and Bolivian defenders found themselves hundreds of kilometers away from home while Chilean invading forces were usually just a few kilometers away from the sea.Chilean ground strategy focused on mobility. They landed ground forces in enemy territory to raid Allied ground assets, landed in strength to split and drive out defenders and left garrisons to guard territory as the war moved north. Peru and Bolivia fought a defensive war maneuvering through long overland distances and relying where possible on land or coastal fortifications with gun batteries and minefields. Coastal railways were available to central Peru and telegraph lines provided a direct line to the government in Lima. When retreating, Allied forces made sure that few assets, if any, remained to be used by the enemy. According to "Chinese Migration into Latin America – Diaspora or Sojourns in Peru?" some Chinese coolies supported the Chilean army against their plantation owners in Peru.[100] As direct consequence of the war several Peruvian towns were shelled, sacked and destroyed.

The occupation of Peru between 1881 and 1884 was a different story altogether. The war theatre was the Peruvian Sierra, where Peruvian resistance had easy access to population, resource and supply centers far from the sea; it could carry out a war of attrition indefinitely. The Chilean army (now turned into an occupation force) was split into small garrisons across the theatre and could devote only part of its strength to hunting down rebels without a central authority. After a costly occupation and prolonged anti-insurgency campaign, Chile sought to achieve an exit through a political settlement. Rifts within Peruvian society and the Peruvian defeat in the Battle of Huamachuco resulted in the peace treaty that ended the occupation.

The war saw the use by both sides of new, or recently introduced, late 19th-century military technology such as breech-loading rifles and cannons, remote-controlled land mines, armor-piercing shells, naval torpedoes, torpedo boats, and purpose-built landing craft. The second-generation of ironclads (i.e. designed after the Battle of Hampton Roads) were employed in battle for the first time. That was significant for a conflict where a major power was not involved, and it drew the attention of British, French, and U.S. observers of the war. During the war, Peru developed the Toro Submarino ("Submarine Bull"). Though completely operational, she never saw action, and she was scuttled at the end of the war to prevent her capture by Chilean forces.

The USS Wachusett (1861) with Alfred Thayer Mahan in command, was stationed at Callao, Peru, protecting American interests during the final stages of the War of the Pacific. He formulated his concept of sea power while reading a history book in an English gentleman's club in Lima, Peru. This concept became the foundation for his celebrated The Influence of Sea Power upon History[101][102].

[edit] World perspectives

Main article: World perspectives of the War of the Pacific

The war remained largely relatively unregarded outside South America because neither the USA nor any major European power participated, although the mineral wealth involved gave Britain and to extent the US, a stake in the outcome[103]. After the beginning of the war, the government of Great Britain declared its neutrality and refused to allow Peru, Bolivia, and Chile to take delivery of military or naval material on British soil.[104]A different matter was the case of persons or companies having some kind of investment in the countries involved in war.

In the 1870s Peru's president Manuel Pardo established a government monopoly to control the sale of nitrate and in 1875 expropriated the salitreras. The Peruvian Government issued interest bearing certificates for the former owners and promised to redeem in two years.[105]

Other group was the "Credit Industrial" and the "Peruvian Company", representing European and American creditors of Peru. They offered to lend the money that Peru required to pay reparations to Chile in order to avoid a Chilean annexation of Tarapacá. In return Peru had to grant mining concessions in Tarapacá to foreigners.[106][107]

Since the nitrate traders and the holders of debts were all aware that they would receive payment only if the war ended, they used their political influenced to push for a quick settlement to the conflict.[108] These groups, and of course others on the Chilean side, acted more or less to obtain a convenient solution for their interests.

[edit] Consequences of the war

The War of the Pacific left traumatic scars on all societies involved in the conflict.[edit] Bolivia

Example of recent expressions of Bolivian irredentism over territorial losses in the War of the Pacific. Eduardo Avaroa statue pointing towards sea, down in the mural it is written; "What once was ours, will be ours once again", and "Hold on rotos (Chileans), because here come the Colorados of Bolivia"

[edit] Chile

Economically, Chile fared better, gaining a lucrative territory with major sources of income, including nitrates, saltpeter and copper. The national treasury grew by 900% between 1879 and 1902 due to taxes coming from the newly acquired Bolivian and Peruvian lands.[110] British involvement and control of the nitrate industry rose significantly after the war.[111] High nitrate profits lasted for only a few decades and fell sharply once synthetic nitrates were developed during World War I.

Territorially, during the war Chile waived most of its claim over the Patagonia in the Boundary treaty of 1881 between Chile and Argentina, in order to ensure Argentina's neutrality during the conflict. After the war, the Puna de Atacama dispute grew until it was solved in 1899, since both Chile and Argentina claimed former Bolivian territories. On 28 August 1929, Chile returned the province of Tacna to Peru. In 1999, Chile and Peru at last agreed to complete the implementation of the last parts of the Treaty of Lima, providing Peru with a port in Arica.[112]

Ericka Beckman argues that socially, during and after the war there was a rise of racial and national superiority ideas among the Chilean ruling class.[113] This can also be exemplified by Chilean historian Gonzalo Bulnes (son of president Manuel Bulnes) who once wrote "What defeated Peru was the superiority of a race and of a history".[114] During the occupation of Tacna and Arica (1884–1929) the Peruvian people and nation were treated in racist and denigrating terms by the Chilean press.[115] According to some authors "there is widespread racism in Chile towards the indigenous peoples of Peru and Bolivia".[116].

Currently, Peruvians are the largest group of immigrants in Chile and increased cases of discrimination, xenophobia and racism among some segments of the Chilean society have been reported.[117][118]

[edit] Peru

According to Bruce W. Farcau "in Peru, the wounds run less deep, than in neighboring Bolivia". On the other hand, George J. Mills argues that after Peru's defeat, "Peruvian resentment, born of the loss of her nitrate territories, is still smoldering."[119] According to military historian Robert L. Scheina, the Chilean plunder of Peruvian national literary and art treasures at the end of the war contributed to "demands of revenge among Peruvians for decades."[120] Scholar Brooke Larson has pointed out that the War of the Pacific was the "first time since independence wars" that "Peru was invaded, occupied and pillaged by a foreign army" and that "no other Andean republic experienced such a costly and humiliating defeat as Peru did in the hands of Chile".[121]

[edit] Bibliography

- Rosales, Justo Abel (1984). Mi campaña al Perú, 1879-1881 (My campaign to Peru, 1879-1881). 1. Concepción, Chile: Editorial de la Universidad de Concepción. http://americas.sas.ac.uk/publications/genero/genero_segunda3_Rosales.pdf. in Spanish

- Gutierrez, Hipólito (1956). Crónica de un soldado de la Guerra del Pacífico (Chronicle of a soldier in the Pacific War). 1. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Editorial del Pacífico. http://www.memoriachilena.cl/archivos2/pdfs/MC0012291.pdf. in Spanish

- Barros Arana, Diego (1881). Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879-1880) (History of the War of the Pacific (1879-1880)). 1. Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Servat i C", Esquina de Huerfanos i Ahumada. http://www.archive.org/details/historiadelague00arangoog. in Spanish

- Barros Arana, Diego (1881). Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879-1880) (History of the War of the Pacific (1879-1880)). 2. Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Servat i C", Esquina de Huerfanos i Ahumada. http://www.archive.org/details/historiadelague01arangoog. in Spanish

- Chilean government (1879-1881). Boletin de la Guerra del Pacifico (Bulletin of the War of the Pacific). Santiago, Chile: Editorial Andres Bello. http://books.google.com/books?id=hH_BiSV-hYkC. in Spanish

- De Varigny, Charles (1922). La Guerra del Pacifico (The War of the Pacific). 1. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cervantes. http://www.archive.org/details/laguerradelpacif00vari. in Spanish (published first time 1881-1882 in Revue des deux mondes)

- Jefferson Dennis, William (1927). Documentary history of the Tacna-Arica dispute from University of Iowa studies in the social sciences. 8. Iowa: University Iowa City. http://books.google.de/books?id=kL0JAAAAIAAJ.

- Paz Soldan, Mariano Felipe (1884). Narracion Historica de la Guerra de Chile contra Peru y Bolivia (Historical narration of the Chile's War against Peru and Bolivia). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Imprenta y Libreria de Mayo, calle Peru 115. http://www.archive.org/details/narracionhistri00soldgoog. in Spanish

- Basadre, Jorge. "Historia de la Republica del Peru, La guerra con Chile (History of Peru, The War on Chile)". http://www.unjbg.edu.pe/basadre/. in Spanish

- Bulnes, Gonzalo (1920). Chile and Peru: the causes of the war of 1879. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Universitaria. http://www.archive.org/details/chileperucauseso00bulnuoft.

- Farcau, Bruce W. (2000). The Ten Cents War, Chile, Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Westport, Connecticut, London: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-96925-8. http://books.google.de/books?id=BsxISMTwsSUC.

- Sater, William F. (2007). Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7.

- Sater, William F. (1986). Chile and the War of the Pacific. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4155-0.

[edit] See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: War of the Pacific |

- Anti-Chilean sentiment

- Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1904 between Chile and Bolivia

- Atacama border dispute

- Chincha Islands War

- Chilean-Peruvian Maritime Dispute of 2006--2007

- Chile-Peru relations

- Puna de Atacama Lawsuit

- War of the Confederation

- World perspectives of the War of the Pacific

[edit] References

- ^ 19,000 in San Juan, 4,000 in Lima, 1,000 in El Callao (Pierola letter to Julio Tenaud) 4,000 in Arequipa, Col. Jose de la Torre Jorge Basadre. History of Republic of Peru

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy

- ^ a b c William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, tables 22 and 23 in pages 348-349. The figures consider neither Chilean POWs (from "Rimac" and "Esmeralda" survivors) nor deserters

- ^ Approving Treaty on offensive and defensive alliance concluded between the Republics of Peru and Chile. Lima: Congress of Peru. 1865 (Spanish)

- ^ a b Boundary treaty between Bolivia and Chile. 1866 (Spanish)

- ^ See Private note of Riva-Agüero to Novoa, November 20, 1872. Godoy papers. Cited in Gonzalo Bulnes, Chile Peru, the causes of the War 1879, page 58 and 59:

- It is desirable that once for all, and as soon as possible, the relations between the two Republics should be defined, because it is necessary to arrive at an arrangement satisfactory to both parties. If Chile dealing with this boundary question seizes the most favourable opportunity to take possession of that coast-line, it is necessary that their plans develop before Chile is in possession of the ironclads under construction, in order that in the definite settlement of this question, the influence, which we are in a position to exert by means of our maritime preponderance may have due weight.

- ^ a b British influence on the salt: the origin, nature and decline. Soto Cárdenas, Alejandro. Santiago : Ed. University of Santiago de Chile, 1998. Page 50

- ^ (See full English version of the treaty in Gonzalo Bulnes, Chile and Peru: the causes of the war of 1879. Imprenta Universitaria. Santiago de Chile.

- ^ See Gonzalo Bulnes, Chile and Peru, The causes of the War of 1879 page 57 and 58:

- The Treaty menaces Chile … Never was Chile in greater peril, nor has a more favourable moment been elected for reducing her to the mere leavings that interested none of the conspirators. The advantage to each of them was clear enough. Bolivia would expand three degrees on the coast; Argentina would take possession of all our eastern territories to whatever point she liked; Peru would make Bolivia pay her with the salitre region. The synthesis of the Secret Treaty was this: opportunity: the disarmed condition of Chile; the pretext to produce conflict: Bolivia: the profit of the business: Patagonia and the salitre.

- ^ See Jorge Basadre, Historia de la Republica del Peru, Tomo V, Editorial Peruamerica S.A., Lima-Peru, 1964, page 2282, "The beginning of the Peruvian naval inferiority and lack of initiative for preventive war":

- Won by Chile's supremacy at sea that year of 1874 contributed to the endeavor to avoid any problem Peru

- ^ See Jorge Basadre, History of the Republic of Peru, Volume V, Ed. Peruamerica S.A., Lima-Peru, 1964, page 2286, "Peru in 1874 and 1878 avoid the alliance with Argentina":

- In August, September and October 1875 ... Peru will hasten to take footdragging and even inhibitory for signing the treaty with that republic [Argentina] in order to retain their freedom of action. The existence of the Chilean ironclads perhaps explains the difference between this attitude and previous

- In 1878 [the Peruvian government] refused to deliver the items ship orders by the Argentine government and collaborate in the search for a peaceful solution…

- ^ Retrospective of landlocked sea. A critical view on how the conflict started. Jorge Gumucio. La Paz, Bolivia

- ^ Chile-Bolivia-Peru: The War of the Pacific. June 2004. Patricio Valdivieso. Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile

- ^ a b Employers, policy, and the Pacific War. Luis Ortega. Santiago de Chile. 1984. (Page 18. File Antony Gibbs & Sons AGA. Valparaiso to Londres. Private N 25. March 6, 1878)

- ^ (Spanish) Boundary Treaty of 1866 between Chile and Bolivia

- ^ a b See Diego Barros Arana, Historia de la Guerra del Pacifico, Vol. I, page 59.

- ^ The Peruvian Historian stated See also Jorge Basadre, here (retrieved on 9 July 2009):

- El desembarco se efectuó sin resistencia, con manifestaciones de entusiasmo. La bandera chilena flameó en todos los edificios del puerto.

- ^ See Gonzalo Bulnes, Chile and Peru, the Causes of the War of 1879 page 42

- ^ War of the Pacific. Gonzalo Bulnes. Antofagasta and Tarapacá. 1911.

Tengo una buena noticia que darle. He fregado a los gringos (se refiere a Mr. Hicks) decretando la reivindicacion de las salitreras i no podran quitarnoslas por mas que se esfuerce el mundo entero. Espero que Chile no intervendra en este asunto... pero si nos declara la guerra podemos contar con el apoyo del Peru a quien exijiremos el cumplimiento del Tratado secreto. Con este objeto voi a mandar a Lima a Reyes 0rtiz. Ya ve Ud. como le doi buenas noticias que Ud. me ha de agradecer eternamente i como le dejo dicho los gringos estan completamente fregados i los chilenos tienen que morder i reclamar nada mas. - ^ See Guillermo Lazos Carmona, History of the borders of Chile, page 65

- ^ History of war in America between Chili, Peru and Bolivia. Tommasso Caivano. 1882

- ^ Valentín Abecia Baldivieso. International relations in the history of Bolivia, Volume 2. La Paz: National Academy of Sciences of Bolivia (Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia). 1986. Page 73.

- But in reality no such declaration of war took place. The decree (Hilarión Daza's decree) to which this characteristic [of declaring war] is attributed only alludes that "Chile has indeed invaded the national territory", stipulating that "all commerce and communication with the Republic of Chile is cut for the duration of the war that [Chile] has promoted upon Bolivia." He later states that Chileans should vacate the country given deadlines in cases of emergency and taking action on property belonging to them. Therefore, it is not correct to attribute that Decree the characteristics of a declaration of war, because under the international law of the time, it was not. The steps taken were for security because Chile had taken Antofagasta. On April 3 the declaration of war by the Chilean Congress was approved, and by the 5th it became known throughout the press.

- Pero en realidad no hubo tal declaratoria de guerra. El decreto al que se le atribuye esa caracteristica solamente alude a que "Chile ha invadido de hecho el territorio nacional", disponiendo que "queda cortado todo comercio y comunicación con la República de Chile mientras dure la guerra que ha promovido a Bolivia". Luego habla de que los chilenos deben desocupar el territorio nacional dando plazos en casos de excepcion y tomando medidas sobre las propiedades que les perteneciera. Por consiguiente, no es correcto atribuir a ese Decreto las características de una declaratoria de guerra, no lo fue. Las medidas adoptadas fueron de propia seguridad ante un hecho consumado por Chile con la toma de Antofagasta. El 3 de abril se aprobó la declaración de la guerra por el Congreso chileno y el 5 se conocía a través de la prensa.

- ^ Ramiro Prudencio Lizon, The Taking of Antofagasta

- ^ Atilio Sivirichi. History of Peru

- ^ (See full English version of the treaty in Gonzalo Bulnes, Chile and Peru: the causes of the war of 1879, Imprenta Universitaria. Santiago de Chile.

- "Republics of Bolivia and Peru, desirous of drawing together in a solemn manner the bonds which unite them, thus augmenting their strength and mutually guaranteeing certain rights, formulate the present treaty of Defensive Alliance; for which object the President of Bolivia has conferred power adequate for such a negotiation to Juan de la Cruz Benavente, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotenciary in Peru, and the President of Peru has conferred like powers to Jose de la Riva-Aguero; who have agreed on the following stipulations:

- Article I. The High Contracting Parties unite and league together mutually to guarantee their independence, their sovereignty and the integrity of their territories respectively, obliging themselves by the terms of the present treaty to defend themselves against all foreign aggression, whether emanating from one or several independent states or from a force without flag and obeying no recognised power.

- Additional Article:

- The present treaty of Defensive Alliance between Bolivia and Peru shall be secret until the two high contracting parties by common accord consider its publication necessary."

- ^ a b c d War of the Pacific. Francisco A. Machuca. Valparaíso "Mientras el señor Lavalle gozaba de relativa tregua, y estudiaba las causas de la poca prisa del Gobierno chileno para continuar las negociaciones, éste, en constante comunicación con nuestro Ministro Godoy, quedaba impuesto el 18 de Marzo, por comunicación del día anterior, 17, de la existencia del pacto secreto, y de una nota clara y terminante de nuestro Ministro al Gobierno de Lima...Por fin, el 31 de Marzo, el señor Lavalle se apersonó al señor Ministro de Relaciones y le dió conocimiento del tratado secreto, que acababa de recibir de Lima, en circunstancia que hacía días, el general Prado le había confesado su existencia a nuestro Ministro Godoy, en una conferencia tenida en Chorrillos."

- ^ Current History (1922) (page 450) The New York Times

- ^ Bulnes, Gonzalo. Chile and Peru : the causes of the war of 1879. pp. 147.

- ^ Guerra del Pacífico, Tomo 1: De Antofagasta a Tarapacá. Page 148. Bulnes Gonzalo.

- ^ Jorge Basadre, Historia de la Republica del Peru, vol. VI, p. 40.

- ^ Peruvian Congress March 24, 1879

- ^ Campana de Tarapacá. Vicuna Mackena. Santiago de Chile

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 113-114.

- "There are numerous differences of opinion as to the ships' speed and armament. Some of these differences can be attributed to the fact that the various sources may have been evaluating the ships at different times."

- ^ a b c d Cap. Jorge Ortiz Sotelo, Miguel Grau, page 70-71.

- ^ Adrian J. English Armed forces of Latin America: their histories, development, present strength, and military potential page 372

- ^ a b c Robert L. Scheina Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791-1899 page 377

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 57

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 48

- ^ Adrian J. English Armed forces of Latin America: their histories, development, present strength, and military potential page 75

- ^ Stanislav Andreski Wars, revolutions, dictatorships: studies of historical and contemporary problems from a comparative viewpoint page 105:

- (...) Chile's army and fleet were better equipped, organised and commanded(...)

- ^ Helen Miller Bailey, Abraham Phineas Nasatir Latin America: the development of its civilization page 492:

- Chile was a much more modernized nation with better-trained and better-equipped

- ^ Robert L. Scheina Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791-1899 pages 376-377

- ^ See Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, Praegers Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, Connecticut 06881, ISBN 0-275-96925-8, Chapter 5, page 65:

- As the earlier discussion of the geography of the Atacama region illustrates, control of the sea lanes along the coastwould be absolutely vital to the success of a land campaign there

- ^ Vargas Valenzuela, José (1974). Tradición naval del pueblo de Bolivia. Bolivia: Editorial Los Amigos del Libro. p. 61. http://books.google.com/books?id=flgSAAAAYAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 102 and ff:

- "… to anyone willing to sail under Bolivia's colors …"

- ^ a b Boletín de la guerra del Pacifico. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Andrés Bello. 1879. p. 288. http://books.google.com/books?id=hH_BiSV-hYkC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 113-114.

- ^ a b c See Mariano Paz Soldan, Narracion historica de la Guerra de Chile contra el Peru y Bolivia, Imprenta y Libreria de Mayo, calle Peru 115, 1884, page 114

- ^ a b Farcau, Bruce (2000). The Ten Cents War: Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9780275969257. http://books.google.com/books?id=BsxISMTwsSUC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ López Urrutia, Carlos (2003). La Guerra del Pacífico, 1879-1884. Ristre Editorial. pp. 37–42. http://books.google.com/books?id=0osTAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Spila, Benedetto (1883). Chile en la guerra del Pacífico. Valparaíso, Chile: Impr. del Neuvo Mercurio. p. 94. http://books.google.com/books?id=Gy8_AAAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Pinochet Ugarte, Augusto (1972). Guerra del Pacífico, 1879. California: Instituto Geográfico Militar. p. 44. http://books.google.com/books?id=6VQOAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Tamayo Herrera, José (1985). Nuevo compendio de historia del Perú. Virginia: CEPAR. p. 285. http://books.google.com/books?id=X2gaAAAAYAAJ&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=2. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Milla Batres, Carlos (1994). Enciclopedia biográfica e histórica del Perú: siglos XIX-XX. Lima, Peru: Editorial Milla Batres. p. 71. ISBN 9789589413005. http://books.google.com/books?id=7sd-AAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Arosemena Garland, Geraldo (1962). El Almirante Miguel Grau. Lima, Peru: Ministerio de Educación Pública. p. 89, 129–131. http://books.google.com/books?id=UKPUAAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Historia marítima del Perú, Volume 2; Volume 11. Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Histórico-Marítimos del Perú. 2004. pp. 188. ISBN 9789972633058. http://books.google.com/books?id=43EKAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Farcau, Bruce (2000). The Ten Cents War: Chile, Peru, and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 214. ISBN 9780275969257. http://books.google.com/books?id=BsxISMTwsSUC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Historia marítima del Perú, Volume 2; Volume 11. Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Histórico-Marítimos del Perú. 2004. pp. 244–246. ISBN 9789972633058. http://books.google.com/books?id=43EKAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ Mellafe Maturana, Rafael; Mauricio Pelayo González (2007). La guerra del Pacífico: en imágenes, relatos, testimonios. Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Centro de Estudios Bicentenario. p. 130. ISBN 9789568147334. http://books.google.com/books?id=KYQTAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ López Urrutia, Carlos; Jorge Ortíz Sotelo (2005). Monitor Huáscar: una historia compartida (1865-2005). Lima, Peru: Asociación de Historia Marítima y Naval Iberoamericana. p. 49. http://books.google.com/books?id=RmVjAAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ Historia del Ejército de Chile, Volume 6. Santiago, Chile: Estado Mayor General del Ejército. 1980. p. 54. http://books.google.com/books?id=SPNjAAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ Luna Vegas, Emilio (1978). Cáceres, genio militar. Peru: Librería Editorial Minerva-Miraflores. p. 19. http://books.google.com/books?id=u4K1AAAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Valdés Vergara, Francisco (1908). Historia de Shile para la enseñanza primaria. California: Sociedad "Imprenta y litografía Universo". p. 319. http://books.google.com/books?id=oFZJAAAAIAAJ&dq=Angamos+Hu%C3%A1scar+capturado+Chile+hundirlo+tripulaci%C3%B3n.&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Milla Batres, Carlos (1994). Enciclopedia biográfica e histórica del Perú: M-P. Michigan: Editorial Milla Batres. p. 73. http://books.google.com/books?id=7sd-AAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Elías Murguía, Julio J. (1980). Marinos peruanos en Arica. Peru: Instituto de Estudios Histórico-Maritimos del Perú. p. 38. http://books.google.com/books?id=2KIKAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Basadre, Jorge (1961). Historia de la República del Perú. Michigan: Ediciones "Historia". p. 2538. http://books.google.com/books?id=9nt-AAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=5. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Calero y Moreira, Jacinto (1794). Mercurio peruano. Peru: Biblioteca Nacional del Perú. pp. 44–46. http://books.google.com/books?id=9nt-AAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_book_other_versions_r&cad=5. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 204:

- "only the lack of allied cavalry prevented Buendia's [Peruvian] men from finishing off the few remaining survivors"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 205:

- "The victorious troops had no choice, as Colonel Suarez ruefully admitted, but to abandon Tarapacá to the Chileans".

- ^ a b c d e f B.W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War

- ^ W.S.Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 181:

- "not only a economic bonanza but also a diplomatic asset that could barter in return for Peru ending the war".

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 120:

- "He [Prado] was met with widespread rioting in the capital in protest over the administration's abysmal handling of the war to date"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The ten Cents War, page 120:

- "…Prado suddenly gathered up his belongings … and took a ship …"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 121:

- "Pierola … mounted an assault on the Palace but … leaving more than three hundred corpses …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 208:

- "Daza received a telegram from Camacho, informing him that the army no longer …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Chile and the war of the Pacific, page 180:

- "Even in the midst of the Bolivian crisis, congressional elections occurred in schedule. In 1881, the nation selected a new president, Domingo Santa Maria, and the following year, elected a new congress"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 130:

- "In the early morning hours of the 31. December 1879 …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 222:

- "Baquedano could not simply bypass the Peruvian troops, whose presence threatened Moquegua as well as the communications network extending southeast across the Locumba Valley to Tacna and northwest to Arequipa and northeast to Bolivia"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau in The Ten Cents War, page 138 specifies 3,100 men in Arequipa, 2,000 men in Arica and 9,000 men in Tacna, but this figures contradict the total numbers given (below) by William F. Sater in page 229

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 138:

- "…it became evident that there was a total lack of the necessary transport for even the minimum amount of supplies and water"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 227:

- "The allied force, he [Campero] concluded lacked sufficient transport to move into the field its artillery as well as its rations and, more significantly, its supplies of water"

- ^ Valdes Arroyo, Flor de Maria (2004). Las relaciones entre el Perú e Italia (1821-2002). Lima, Peru: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru. ISBN 9974-42-626-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=DGexys3TxhQC&pg=PA97., page 97, in Spanish language

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 152:

- "Lynch's force consisted f the 1° Line Regiment and the Regiments "Talca" and "Colchagua", a battery of mountain howitzers, and a small cavalry squadron for a total of twenty-two hundred man"

- ^ Diego Barros Arana, Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879-1880), volume 2, page 98:

- "[The Chilean government thought that it was possible to demonstrate to the enemy the futility of any defense of Peruvian territory not only against the whole [Chilean] army but also against small [Chilean] divisions. That was the purpose of the expedition, which the claims, insults, and affliction in the official documents of Peru and in the press had made famous"

- (Original: "[El gobierno chileno] Creía entonces que todavía era posible demostrar prácticamente al enemigo la imposibilidad en que se hallaba para defender el territorio peruano no ya contra un ejército numeroso sino contra pequeñas divisiones. Este fué el objeto de una espedicion que las quejas, los insultos i las lamentaciones de los documentos oficiales del Perú, i de los escritos de su prensa, han hecho famosa.")

- ^ Jorge Basadre, "Historia de la Republica del Peru", Tomo V, Editorial Peruamerica S.A., Lima-Peru, 1964, page 2475,

- ^ Diego Barros Arana quotes Johann Caspar Bluntschli:

- "Bluntschili (Derecho internacional codificado) dice espresamente lo que sigue: Árt. 544. Cuando el enemigo ha tomado posesión efectiva de una parte del territorio, el gobierno del otro estado deja de ejercer alli el poder. Los habitantes del territorio ocupado están eximidos de todos los deberes i obligaciones respecto del gobierno anterior, i están obligados a obedecer a los jefes del ejército de ocupación."

- ^ John Lawrence Rector The history of Chile page 102

- ^ Jason Zorbas The influence of domestic politics on America's Chilean policy during the War of the Pacific page 22:

- "The Chilean public demanded that Lima be taken. Bloodlust ran high, as some of the press demanded that the Moneda (the Chilean equivalent of the White House) ""exterminate the enemy the same as Great Britain and Argentina had annihilated the Zulus and the Indians."" The government struggled to satisfy the public demands for an invasion. During the last months of 1880, the Chilean armed forces prepared for a full invastion of Peru and as the new year arrived the Chilean forces were poised outside Lima and prepared to invade the capital"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 149-150:

- "Despite this expectations …"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 157:

- "… until all vestiges of organized military force in Peru had been destroyed and the capital occupied"

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 157 gives 26,000 men but William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 274, gives 25,000 to 32,000 men

- ^ a b Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 164:

- "This gave Baquedano some twenty thousand men in the assault with a further three thousand in reserve against about fourteen thousand Peruvians in the line with twenty-five hundred in reserve"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 302:

- "which he [Nicolás de Piérola] did not"

- ^ John Edwin Fagg Latin America: a general history" page 860

- ^ Steve J. Stern Resistance, rebellion, and consciousness in the Andean peasant world page 241

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 312:

- "Consequently, the court stripped Letelier of his rank, sentenced him to six years in jail, and demanded restitution"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 304-306:

- "The anglophobic secretary of state …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Chile and the War of the Pacific, page 220:

- "Since Montero was not a party to the Treaty of Ancon …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 90:

- "Happily for the wounded the three warring nations adhered to the Geneva Convention."

- ^ http://www.history.appstate.edu/ConferencePapers/dorotheamartinpaper.pdf

- ^ The Ambiguous Relationship: Theodore Roosevelt and Alfred Thayer Mahan by Richard W. Turk; Greenwood Press, 1987. 183 pgs. page 10

- ^ Larrie D. Ferreiro 'Mahan and the "English Club" of Lima, Peru: The Genesis of The Influence of Sea Power upon History', The Journal of Military History - Volume 72, Number 3, July 2008, pp. 901-906

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page2:

- "it has largely been ignored outside the region as neither the USA nor any major European power had a stake in the game"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 85:

- "Great Britain, for example, refused to allow Chile to take delivery of military or naval supplies on English soil."

- ^ William F. Sater, Chile and the War of the Pacific, page 127:

- " In 1875, hagridden by financial problems, …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy, page 305:

- "An the sudden appearance of two previously unknown corporations - the Credit Industrial and the Peruvian Company - …"

- ^ William F. Sater, Chile and The War of the Pacific, page 210 and ff

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War, page 149:

- "Another factor working in favor of a quick settlement to the conflict was the influence of the neutral powers …"

- ^ "El día del mar se recordará con más que un tradicional desfile cívico" (in Spanish). Bolpress. 15. p. 1. http://www.bolpress.com/art.php?Cod=2006031515. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Crow, The Epic of Latin America, p. 180

- ^ Foster, John B. & Clark, Brett. (2003). "Ecological Imperialism: The Curse of Capitalism" (accessed September 2, 2005). The Socialist Register 2004, p190-192. Also available in print from Merlin Press.

- ^ Dominguez, Jorge et al. 2003 Boundary Disputes in Latin America. United States Washington, D.C.: Institute of Peace.

- ^ Ericka Beckman Imperial Impersonations: Chilean Racism and the War of the Pacific University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- ^ Bruce W. Farcau The Ten Cents War page 169

- ^ William E. Skuban Lines in the sand: nationalism and identity on the Peruvian-Chilean frontier page 79:

- "because it is undoubtedly preferable to be Chilean than Peruvian, because has a cleaner and more glorious history, and its better to belong to the phalanx of the conquerors than that of the conquered, because the Chilean race is more virile, valiant, prouder, nobler and more enterprising than the Peruvian race, which due to reasons of climate will always be enervated" Chilean newspaper El Corvo quote in page 80

- ^ Toby Green, Janak Jani Footprint Chile 2006, page 524

- ^ Peruvians in Chile: the challenge of intercultural education

- ^ Teun Adrianus van Dijk Racism and discourse in Spain and Latin America page 123:

- "with the current immigration of workers from Peru and Bolivia, there is also increasing racism against these minorities..."

- ^ Chile: physical features, natural resources, means of communication by George J. Mills, William Henry Koebel (page 39)

- ^ Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791-1899 by Robert L. Scheina (page 388)

- ^ Larson, Brooke. 2004. Trials of Nation Making: Liberalism, Race and Ethnicity in the Andes, 1810-1910. Page 178.